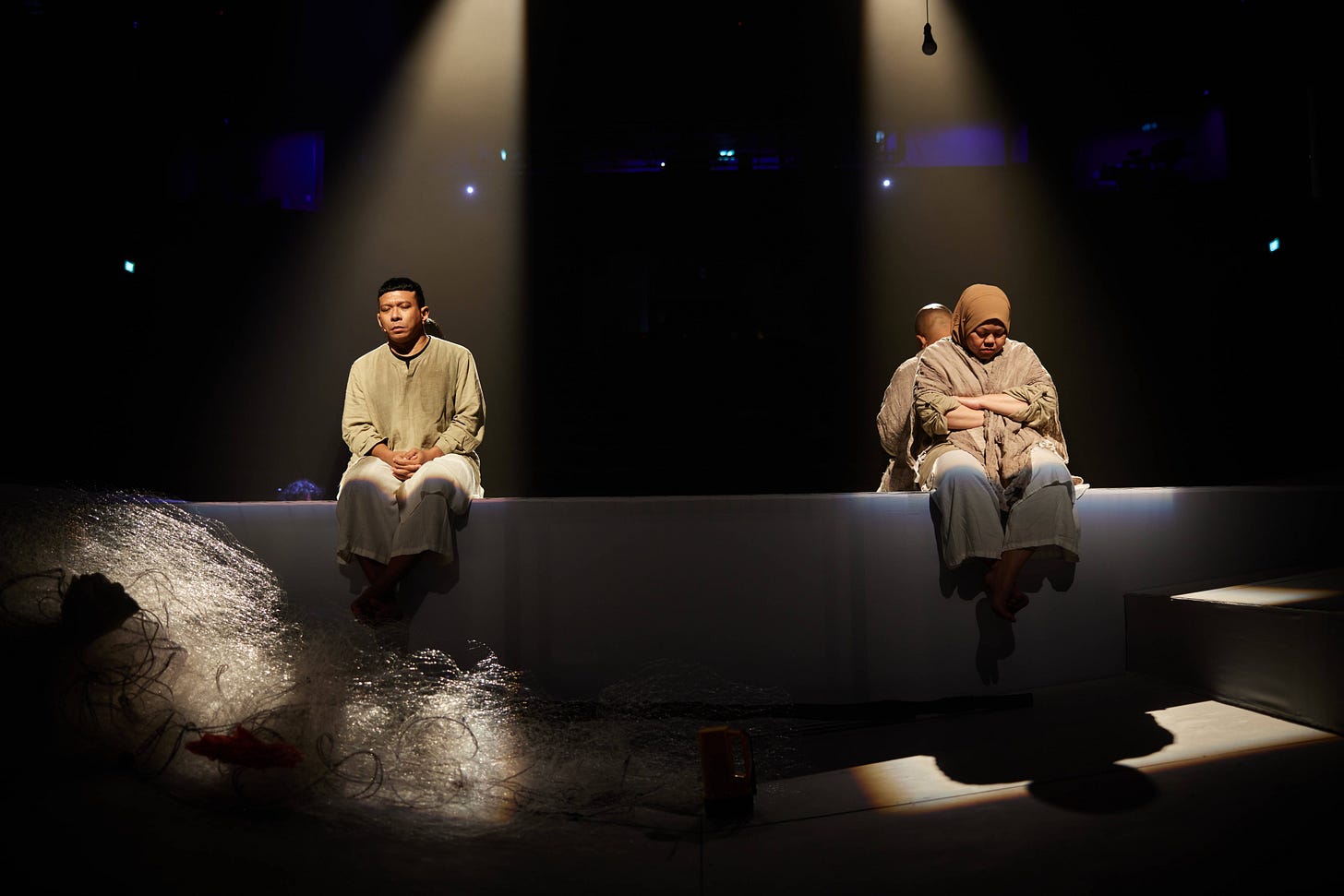

“Air” by Drama Box

On the Orang Seletar, the stewardship of the sea—and the stewardship of stories.

I’ve just come back to Singapore from a long trip across the UK, where I spent several days crewing aboard a gorgeous old boat called the Marian. She’s a 135-year-old Bristol Channel pilot cutter, one of eighteen left in the world. I’m relatively new to sailing, and one of the first navigational maneuvers I had to learn as we circled the Cornwall coast was called “tacking”.

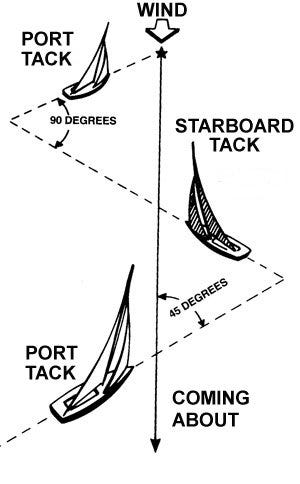

Say you want to head in a specific direction, but the wind isn’t in your favour. You’ll move the bow of your boat toward and through the wind so that the direction of the wind changes from one side of the boat to the other, pushing you in the right direction and out of the “no-sail zone”. Often you’ll have to travel in a zig-zag fashion, which means that it looks like you’re going the wrong way, but you’re really right on track. Working with the elements, instead of fighting them, gets you there faster—even if it may not always feel like it.

Sailing makes you recognise two things pretty quickly: that the water and the weather can toss a 50-foot, 28-ton boat around like a small plaything; and that the people you’re sharing several feet of space with will become your family. You’ll learn their waking habits and sleep patterns, their footfalls on deck and the timbre of their snores. Intimacy and terror make a ripe combination for ritual.

One of the most moving rituals in Drama Box’s Air (Malay for “water”, pronounced ayer) involves tying a mother’s placenta to a mangrove tree as a charm to prevent children from drowning. The intimacy of your body’s viscera, warding off the terror of a mercurial body of water. Over the past few years, the socially engaged theatre company has been developing this piece of verbatim theatre to foreground the stories of the dwindling Orang Seletar1 community. They first staged it as part of a doublebill in 2019 at the Malay Heritage Centre, which I’d brought my Theatre Criticism students to watch and respond to. This year, Air is part of the Esplanade’s Studios season at the Singtel Waterfront Theatre.

What I love most about this quiet, understated piece is the company’s commitment to working with a marginal community as respectfully and equitably as possible, even if the theatrical “tack” they’ve taken requires an enormous investment of time, effort and windward detours.

I didn’t arrive at Air expecting to write a response to it, so instead I’ll offer you an handful of little thought-islands, fragments of feeling, assembled together in an archipelago of writing.

i. on land and legitimacy

“The sea is no more. Everything is about the land now.”

We feel this absent sea by way of an absent boat. We’re arranged, like two parallel breakwaters, on either side of Fared Jainal’s set. The white structure slopes downward, almost as if it’s a wave caught mid-ebb, and I think of the actors as walking on water, or floating where the deck of a pau kajang2 might be. Later on, they’ll descend into the metaphorical sea’s murky depths through a series of trap doors.

Here, land isn’t just location—it’s a position from which power is meted by terrestrial mandate. Schools, medical care, legal processes, citizenship: all land-based administrative processes that demand the subordination of those accustomed to adjusting their movements, needs and desires to a wilful sea. But it seems like the sea is easier to appease than the land. One of the Orang Seletar describes a tense encounter with a Singaporean patrol when gathering her drifting nets; she’d inadvertently crossed a maritime border and couldn’t understand what kind of threat she, an elderly fisherfolk, might pose to an affluent nation-state and its military representatives. Another doesn’t understand why marriage and birth certificates are necessary: if you sleep together, you’re spouses; her father was her mother’s midwife aboard their family boat.

Historian and anthropologist Jennifer Gaynor writes about a period of intertidal history up to the 1950s that still offered sea nomads some degree of political agency, where forging social connections with sea nomads conferred states nautical advantages, as well as maritime skills and networks.

Air’s researcher Ilya Katrinnada echoes this in her recent conversations with the Orang Seletar:

Jefree’s mother, [Leiti]3, told us that Tok Batin Buruk once used his spiritual prowess, along with a handkerchief, to help the then sultan of Johor court the Princess of Kelantan. This story reflects the close patron-client relationship between the Orang Seletar and the sultan in the past. Before World War II, they worked for the sultan, who paid them to catch crabs and fishes. They also often received invitations to the palace and accompanied the sultan on his hunting trips.

But we’ve entered a time where the power asymmetry between land and sea is so dramatic that the itinerant seafarers have hardly any leverage over these political and socioeconomic negotiations. The spectre of Danga Bay looms large over Air and its inhabitants. The residential-commercial development forms the deepest undercurrent of resentment in Air, as fishing territory is curtailed and ancestral cemeteries are flattened to make room for luxury and profit.

ii. on the stewardship of stories

“There’s no use in me telling all these stories.”

The opening scene of Air is an exercise in performing self-reflexivity. Each of the actors is listening to recordings of their Orang Seletar interviewees, whose oral cadences, physicalities and emotional landscapes they will soon inhabit. The soft lilt of their Kon-inflected Malay sits uncomfortably in the actors’ mouths. We are merely conduits, is what I imagine the actors and creative team saying, we are vessels for lives we hold dear to ourselves, but whose histories and experiences we cannot even begin to imagine. Or: we may be members of a minority group, but here we are, enacting the lives of those even more marginal. It’s a dilemma every researcher faces when engaging with a marginal community as out-group rather than in-group members: how much of yourself to centre, when your presence and experience is central to communicating the group’s struggles to others?

Demonstrating reflexivity as a methodological device is something feminist anthropologists (the likes of Lila Abu-Lughod, Ruth Behar and Elizabeth Enslin) have long advocated in their writing. The research that Drama Box embarks on for their long-term projects can feel both anthropological and sociological in scope, with artists as committed participant-observers in the communities whose stories they hope to give theatrical shape to. Air’s co-director Kok Heng Leun has often characterised his performance development processes as involving acts of “deep hanging out”, a term popularised by anthropologist Clifford Geertz; playwright Zulfadli Rashid (or “Big”, as he’s more affectionately known), playing the ethnographer, sifted through hundreds of hours of interviews and field recordings to gather the complex thematic strands into a cohesive narrative. Their work echoes Ruth Behar’s ethos of vulnerability:

Since I have put myself in the ethnographic picture, readers feel they have come to know me. They have poured their own feelings into their construction of me and in that way come to identify with me, or at least their fictional image of who I am. These responses have taught me that when readers take the voyage through anthropology’s tunnel it is themselves they must be able to see in the observer who is serving as their guide. When you write vulnerably, others respond vulnerably.

—from The Vulnerable Observer (1996)

Air (co-directed by Adib Kosnan) revels in revealing the “backstage” workings of this project, whether it’s the vulnerability of actors preparing for their roles, or sound designer Tini Aliman performing live from her tiny sound booth: drumming on an inverted plastic carton and drawing a slow bow across a violin. Multimedia designer Jevon Chandra’s surtitles linger and fade on the sides of the stage, like the watermarks on a boat’s hull or a pier’s columns. Each of the Orang Seletar narrators employs repetition as an unconscious rhetorical device, and the surtitling gives visual anchor to their repeated words and phrases. Whether ketam (crab) or cerita (story), there’s a sense through these lexical refrains that all of these stories have been told before: repeated to children at bedtime, repeated for government reps, repeated to researchers mining for data. What’s the use of telling these stories if none of them are transmuted into some kind of action? In one of the most emotional post-show dialogues I’ve ever experienced, each of the actors broke down in tears as they grappled with the enormity—and the impossibility—of the work’s ambition. Did we do these stories justice? they ask, over and over again.

iii. on the stewardship of the sea

Watching Air made me recognise something I’d always known but never felt: the inextricability of indigeneity and ecological maintenance. Everything the Orang Seletar do is contingent on the resourcing of the earth; the effects of polluted seawater ripple outwards as their catches of mussels and crabs, once bountiful, now can barely sustain a single family.

Mariam Ali analysed the Orang Asli’s cultural orientations towards the environment and arrived at four categories:

Type 1: People viewed themselves as part of nature and as always in harmony with it. This could be seen among the nomadic Orang Seletar, whose intrusion upon nature was minimal and renewable, being based on a long-established subsistence mode of appropriation.

Type 2: People viewed nature with reverence. Harmony was sought through attempts at pacifying nature. Nature became increasingly anthropomorphized – as having a consciousness of its own – and could not be taken for granted. One had to learn how to live harmoniously with this consciousness because one was dependent on it. This orientation was followed by the sea-dependent groups such as the Orang Kallang, the Orang Selat and the Orang Johor. One’s luck in life very much depended on the moods of nature which one had to constantly be conscious of “trespassing”. […] No one owned anything in nature because it had its natural guardians […]. People could at best borrow from the guardians and never possess anything without their approval.

Type 3: Nature was increasingly anthropomorphized, but in terms of forces which were out to create mischief against people. Therefore, people were fearful of the forest, the sea and the swamp because these were non-human areas inhabited by evil spirits and ghosts. They tried to stay out of these places, and made use of more powerful forces (such as God) to help contend with the spirits and ghosts. This mode was typical of most of the Malays, who had little to do with the natural environment directly, as they relied on wage labour for their survival.

Type 4: Nature was something to be manipulated and controlled. This mode displayed indifference and extreme detachment from nature, and was espoused by those who did not depend directly on nature for survival, were not in direct contact with it, but had nevertheless an interest in deriving the optimum benefit from its exploitation. This could be said to be the attitude of the state and other impersonal social organizations such as big corporations.

—from “Singapore’s Orang Seletar, Orang Kallang, and Orang Selat: The Last Settlements” by Mariam Ali

We have become so divorced from alam that many of us might identify as “Type 4” (or complicit with corporations and states who are) at this point. One of the characters wonders aloud why the Orang Seletar never owned or claimed land and property. Can we even say that we own anything in Singapore today, as our leases creep towards expiry, and our forests are bulldozed to make way for more columns of temporary homes? Living as lightly on the land as we can becomes part of caring not just for a faceless demographic—but our neighbours who occupy the thin sliver of water separating this island from the peninsula.

iv. on ilmu and magical knowledges

“We don’t want to learn it because we prioritise eating.”

When sociocultural anthropologist Cynthia Chou first embarked on her decades-long research work with the Orang Suku Laut, she was cautioned by well-meaning Malay and Chinese informants from Riau to avoid the seafaring community for fear they would “bewitch” her with their powerful black magic (ilmu hitam). She writes:

Invariably, I was cautioned that I, as someone from another world, was completely ignorant in comparison to the ‘people of Indonesia’ who know that ‘the Orang Laut possess no religion and do not pray at all.’ These concerned Indonesians were worried that I would be bewitched and poisoned by the Orang Laut, whom they believed to possess the most powerful form of ilmu hitam (black magic). The usual scenario painted for me by my well-wishers was that I would be bewitched into forgetting and abandoning everything about myself and my family ties, and finally marrying an Orang Laut.

—from Indonesian Sea Nomads: Money, Magic and Fear of the Orang Suku Laut (2003)

Chou, of course, eventually found these stereotypes to be completely untrue.

But even the reach of ilmu is fading as newer generations of Orang Laut struggle to make time to hone its craft. Its power, fickle and unruly, can’t be tamed by hobbyists and amateurs; it requires devotion, and the Orang Laut require food, and jobs, and money. Organised religion, which many of them have accepted and converted into, is also more governable than the chaos of magic. “We don’t want to learn [ilmu],” one of them says in the play, “because we prioritise eating.” It’s a line that breaks my heart.

All these eroding knowledges, fading from lack of use, fading from the administrative assimilation of diverse Orang Asli indigenous communities into the reductive racial taxonomies we’ve maintained. All of our bodily wisdoms, it seems, can’t ward off the impending flood of hypercapitalism, hyperconsumerism, and the ecological tidal wave these twin terrors have forged in their wake.

Yet Air is larger than the performance excerpt we see. In pre-show conversation, members of the Orang Laut community spoke about filing a 2012 civil suit against developers, as well as the state and federal governments, for their right to remain on their ancestral lands and waters. They were granted customary rights in 2017, then reached an agreement in the legal battle last year to have an area gazetted as an Orang Asli reserve. The development company would also bear the costs of this new settlement.

I’m struck by the magic of the radical hope that remains: that amidst almost certain destruction there is a pride in renewal and collective action. That there remain these porous places of enchantment where our bodies are knitted to nature, these seams of silver rivers where arbitrary geopolitical borders might be ignored, and drifted through. Air is both narrative tributary and tribute to a way of life that is at once mourned and celebrated—where grief might mobilise us and joy might buoy us in a broken world that is our responsibility to repair.

v. postscript: recommended reading

Intertidal History in Island Southeast Asia by Jennifer Gaynor

Indonesian Sea Nomads: Money, Magic and Fear of the Orang Suku Laut by Cynthia Chou

Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural and Social Perspectives, edited by Geoffrey Benjamin and Cynthia Chou

“The Orang Seletar: Rowing Across Changing Tides” by Ilya Katrinnada

“Photo Essay: Changing Tides, Staying Grounded” by Ilya Katrinnada and Jefree Salim

I watched Air on July 13th at 3pm. The post-show dialogue was moderated by dramaturg Charlene Rajendran. It was hard not to cry.

Disclosure: I’m currently working with Drama Box as writer-in-residence/critical documenter for a different long-term project, Project 12, based on Pulau Ubin. I’ve worked frequently enough with the group at this point that I will no longer be reviewing their work formally, but am of course delighted to continue writing about them on this personal blog.

This post was completed as part of the 2024 ArtsEquator Fellowship.

Here, I use “Orang Seletar” to refer to a specific indigenous community moving through the straits of Johor. “Orang Laut” is an umbrella term for a broader seafaring group of indigenous peoples, while “Orang Asli” is an official term broadly used to denote indigenous ethnic groups in Malaysia.

A pau kajang is a wooden boat that typically houses a family of around six people.

Leiti’s name is spelled “Letih” in several transcripts and articles.