Tattooing and the aesthetics of care

A short affective history of the artwork on my body—and how it has been received

Yes, I know I’m supposed to be working on my PhD dissertation. But as I was telling a friend—sometimes you need to write something else to loosen other kinds of writings… So here’s a random newsletter on one of my deep pleasures: the act of tattooing. Enjoy the detour :)

I. “the forms of the skin are a living history of this other’s encounter with other others”

I’ve always been curious about what it is that people choose to remember on their bodies. I once met a fellow academic who had a small line of crests tattooed down his right wrist, one for each site that had shaped him. He glanced down at his wrist when I asked him about it, and I could see him reaching back across each stretch of his life to explain how they had come to be represented by a single symbol. I love asking about tattoos because they immediately produce intimate conversations; I’ve had people pull up their shirts and pull down their trousers in public, completely unselfconsciously, just to show me the cartographies of their lives on their bodies and how they arrived there.

There’s something so unabashed about how the skin is revealed that always speaks to me; how some parts of the body are always available to the public and others reserved for a select few. Sara Ahmed writes so beautifully about what the skin is and what it does in one of her earliest books, Strange Encounters: Embodied others in post-coloniality (2000; I’ve quoted from the same book in the heading for this section). Her writing is pretty dense, so I’ll reflect on it after the quote in the way that I understand it:

if the skin is a border, then it is a border that feels. In the work of Jennifer Biddle […] the skin ‘as the outer covering of the material body’, is where the intensity of emotions such as shame are registered (1997: 228). So while the skin appears to be the matter which separates the body, it rather allows us to think of how the materialisation of bodies involves, not containment, but an affective opening out of bodies to other bodies, in the sense that the skin registers how bodies are touched by others. Sue Cataldi’s concern with skin as an ‘ambiguous, shifting border’ centres on the question of how our skin ‘paradoxically protects us from others and exposes us to them. How we touch and how we are touched affects us’ (1993: 145). The skin provides a way of thinking about how the boundary between bodies is formed only through being traversed, or called into question, by the affecting of one by an other. (p. 45)

I love thinking about the skin as something that doesn’t just hold us in and contain us and separate us from others—the border of who we are—but also something that opens us out to others, exposes us to them. Borders both prevent us from crossing and allow us to pass through. I am alerted to unwanted, intrusive, transgressive touch as much as I open myself to receive and welcome other kinds of touch and the immediate feelings that accompany these touches. My cat brushing against my legs. Someone leaning in, too close, on the train. The embrace of an old friend. An almost-lover’s electric fingers on the elbow or the knee. And then thinking about how two entirely different sets of feelings might be produced in each person by a mutual touch. When I think about a tattoo, I suppose it isn’t just the aesthetics of the image that reveals who you are on your skin, but the kinds of emotions or affects registered within that image, marked on the border of who you are.

I have two small tattoos and two large-scale ones, in both colour and black & grey. Over time I’ve started to curate my tattoos the way I would a small art collection, deciding what to invest in, what to commission, who to collaborate with, what kind of placement might be best for the work I love, while also leaving room for more. Everyone I’ve met approaches tattoos differently; each tattoo might be marked by delight, regret, nostalgia, euphoria, remembrance, pain. This essay is a way of making sense of how these feelings are tattooed onto that porous, fleshy surface that connects us to the rest of the world—and the (aesth)ethics of the process.

II. “Towards an aesthetics of care”

The first tattoo I received was by Sophia Baughan (Sydney, Hand in Hand Tattoo), who happened to be doing a guest spot in London while I was living there in 2017. I was coming to the end of my stay in the UK, and wanted something small imprinted on my body of the city that had become a second home. The tattoo is of a male bearded reedling, a common species native to the UK, perching delicately on a reed. I still hadn’t quite decided how visible I wanted my tattoos to be, so I chose a spot on my left bicep that’s easily covered up, but also allows the bird to peek out:

What I remember most about receiving this first tattoo was the cipher of the artist-client relationship I was introduced to that I had no prior key for—what to do when arriving at the tattoo studio, whether the stencil for the tattoo could be altered, the unspoken pressure to make a final decision, how much I could make conversation with my artist, and an understanding of the kind of pain a body can take. To permit the border of your body to undergo this kind of trauma requires a special sort of relational contract, where somehow, somehow, the tattoo artist—often a complete stranger—is invited to create and share in this space of intimacy. It’s also a space of nonsexual physical intimacy often occupied by family, medical professionals, or anything to do with the rehabilitation of the body through acupuncture, physiotherapy, massages. Each artist sets up this space differently; I’ve begun to seek out artists who make the environment for receiving a tattoo as safe and welcoming as possible, from the moment the booking process begins. The stereotype of the tattoo studio as a grungy, subculture, hypermasculine space has all but disintegrated at this point, but much of the debris remains.

Most of the artists I’m drawn to encourage clear communication, including stating their prices clearly, and they welcome all genders, sexualities and body types, as well as skin tones. I’ve met so many friends with more melanated skin who are hesitant about getting tattoos because so few artists take the time to understand how colour works on skin, and how to adjust colour so that it shows up on darker-toned skin beautifully and clearly. One of my favourite artists, Esther Garcia (who’s based in Chicago), has been posting her experiments with adjusting colour schemes to a range of skin tones; she’ll often invite clients to participate in her experiments for free to dismantle the systemic racism lodged at the heart of the industry.

The same goes for body type, and how the process of tattooing can be undergirded by embarrassment and insecurity for those who don’t feel they have the “right” kind of body type to receive a work (real talk: tattoos are for all bodies; the tattoo should fit the movement and curves and angles of your body, not the other way round). In London/Brighton, Daniel the Gardener has made it a point to showcase his gorgeous, William Morris-inspired freehand tattoos on an entire range of bodies.

So much of the work these artists do is care work made visible. Discourse about care work often entails a lot of discussions about the tedious, difficult work that is under-valued (domestic work, housekeeping, cleaning, etc.). But we can credit performance and live art for creating an aesthetics out of these maintenance processes—the most famous, of course, being the work of artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who in the 1960s-1970s started doing household chores in the museum and “elevating” them to the status of art; she also worked with several hundred maintenance workers (janitors, cleaners, etc) to document the kind of daily work they were doing as art. More recently, theatre scholar James Thompson has reignited discussions about “an aesthetics of care”, where we can observe a quality of the deeply beautiful in the practised gestures of care workers. In his article “Towards an Aesthetics of Care” (2015), he describes observing a physiotherapist at work rehabilitating one of his friends who had been involved in a traumatic incident of armed conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo:

Antoine required at first daily exercise on the joints in his shoulder, elbow, wrist and individual fingers. This was extraordinarily painful and needed a clarity of purpose, mutual respect, intimacy and quality of touch that I found breath-taking. The relationship that developed and the tireless, joint-by-joint work was intense and demanded a kind of eyeball-to-eyeball trust between patient and carer. My wife and I found ourselves using the same word as we struggled to capture the quality of this relationship: independently of each other, we referred to it as beautiful. We, thus, both used aesthetic criteria to judge the exceptional in this example of care. We were drawn to some quality in the touch, the attentiveness and the focus of the relationship that demanded to be appreciated using a language more usually associated with artistry. (pp. 37-38)

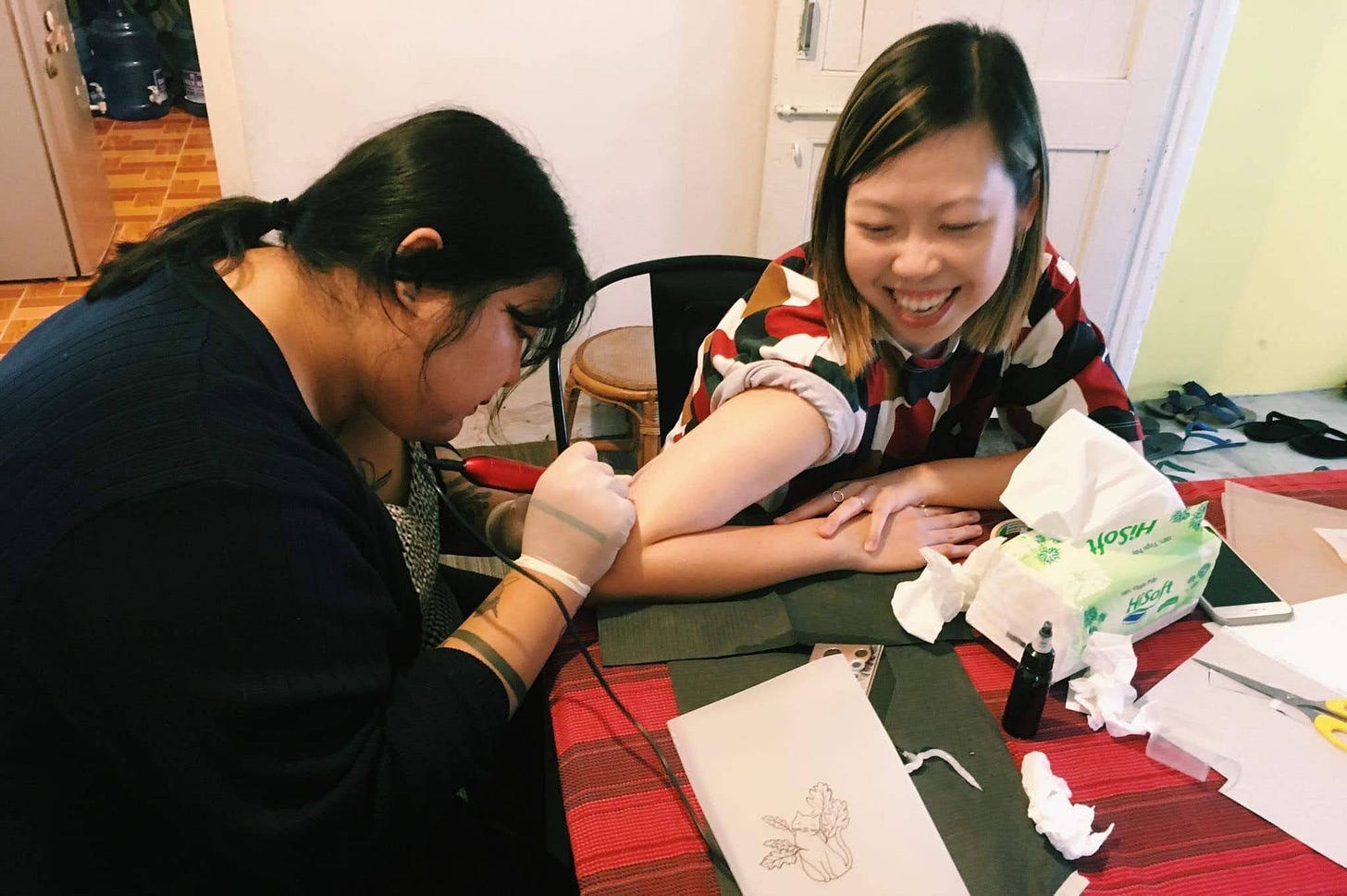

The artistry of the tattoo artists who work on the canvas of our skin is then not confined to the artwork produced—but also the quality of their engagement with us, and their sensitivity to the way the body reacts to pain, the various degrees of undress required depending on the placement of the tattoo, the privacy afforded these moments of physical vulnerability. I have had the privilege of working with two artists who are deeply committed to these care practices, even if they don’t articulate them explicitly: Maxine Ng (Singapore; Iron Fist Tattoo) and Eli Lucii (Trowbridge, UK; Alchemilla Tattoo). I have a feeling that valuing an aesthetics of care in tattooing is very gendered, and that female/queer tattoo artists are largely those who place an emphasis on these processes. Both Maxine and Eli had clear boundaries about the kind and amount of client work they could take on, were infinitely patient about adjusting the work to suit my body, and attentive to my aftercare worries—Maxine patiently walked me through a massive allergic reaction to the adhesive bandage Saniderm that’s often used in tattoo aftercare; in Eli’s case, part of my tattoo healed very poorly (no one’s fault, just my skin reacting), which she was mindbogglingly kind about and responsive to. An aesthetics of care is then both the practice of the artist and also their disposition towards the people they work with.

III. “the sociality of pain”

In this final section I’m going to deal with something that’s constant throughout tattooing—pain. I’m citing Sara Ahmed again, this time from one of her big seminal works, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (2004). Ahmed talks about how pain often turns the body inward, while pleasure opens up our body to other bodies. But tattooing sits suspended between pleasure and pain, linking the pain of the experience to the pleasure of the image created and then again to the complex ways in which we are perceived by and connect with others through the border of our skin. I suppose that is what bodily rituals usher us through, and tattooing is often part of rituals that mark a coming-of-age or milestones in one’s life. I’ve been tattooed by artists who use numbing creams and artists who don’t, but either way I’ve received work on particularly sensitive parts of my body that have compelled me to regulate my breathing and pay attention to where I’m holding tension as I anticipate the path of the needle, and allow myself to sit with the pain just as it is.

The body is a remarkable receptacle for pain, whether this is physical or emotional pain. Pain is contingent on so many things; the word contingent itself has the same Latin root as the word contact (contingere: com, with; tangere, to touch). About five years ago I went for a vipassana silent meditation retreat that was simultaneously one of the most excruciating and most transcendent experiences I’ve had in my life, largely because it taught me how to observe both physical and emotional pain, and how they manifest and subside within my body and heart. We meditated for ten hours a day, waking up at 4.30am and sleeping at about 9pm, and for the first few days I considered all the ways in which I might run away. I could not face my body and all the joints and muscles screaming from the discipline of sitting, straight-backed, for hours. Neither could I face the anxious snarl of my own mind.

Tattooing does feel like a similar physical experience. I’ve often felt delirious post-tattooing from concentrating so hard on observing my pain for hours—and of course you’re also bleeding a fair amount for large-scale work. Getting a tattoo is really like getting skin surgery; the needle leaves ink in the dermis layer of the skin, below the epidermis layer on the surface. Your body’s immune system goes, oh shit, there’s a foreign substance in my system, and immediately gets to work producing phagocytes to protect you. The tattoo will leak substantial amounts of clear plasma for about 24 hours and, as it heals, the damaged top layer of the epidermis will scab over and flake off, leaving the stable pigment beneath. It can be a messy, bloody, painful, itchy process (especially for colour tattoos) requiring a lot of care in the shower, clean hands, kitchen towels, unscented moisturiser, cling wrap, and medical tape. The tattoo looks awful and scabby for a couple weeks until the body is satisfied with its healing process. That first time, there’s really also no sense of how your skin might choose to heal. This terrifies me the most, being at the mercy of how my skin decides what stays and what goes. I’m still gripped by anxiety every time the wrap comes off and the body does its work, because it is one of the few things that really exists beyond my control. I can create some of the conditions for healing, but the rest is time, and trust.

When I see the tattoos of others I sometimes think about our shared pain, held here on the surface of our bodies. When meditating, I thought a lot about how physical pain and emotional pain might be more alike than I anticipated. Ahmed writes about the “sociality of pain” and how we are compelled to hold or touch the pain of others:

The sociality of pain – the ‘contingent attachment’ of being with others – requires an ethics, an ethics that begins with your pain, and moves towards you, getting close enough to touch you, perhaps even close enough to feel the sweat that may be the trace of your pain on the surface of your body. (p. 31)

What are the things tattooed within our bodies and the bodies of others that so few of us are privy to? I suppose that requires an eversion of the self, turning ourselves inside-out. I respect the pain that others choose not to disclose, but I also acknowledge that it exists, printed and scarred on the undersides of our skin. I spoke to a close friend of mine who has several impulsive tattoos she got as a young woman, and she said: “Well, it was either tattoos or self-harming.” I felt that in the pit of my chest. I’ve seen gorgeous tattoos that decorate and memorialise mastectomies of breast cancer survivors. Tattoos that overlay scars either from the self or from others, including significant events such as top surgery. Tattoos that cover up the histories of other tattoos, of previous selves. All of these contingent emotions knit through by the needle of the artist, and the reassurance that to be touched by pain can be transmuted through tattooing into the touch of delight.

The damage of emotional pain, like the damage of the skin, heals in all kinds of unexpected ways. I think about the phagocytes rushing to the site of trauma, the skin growing over itself, and the repeated refrain of all tattoo artists: that you absolutely should not touch the tattoo or worry the scabs throughout the process. The time it takes is the time it takes, and picking at the skin, no matter how satisfying, will only cause it more harm. Tattooing isn’t a salve for all pain and grief. But I am now so appreciative of what this process—one stretching back thousands of years—can offer to us as a conduit for processing pain through pain itself.