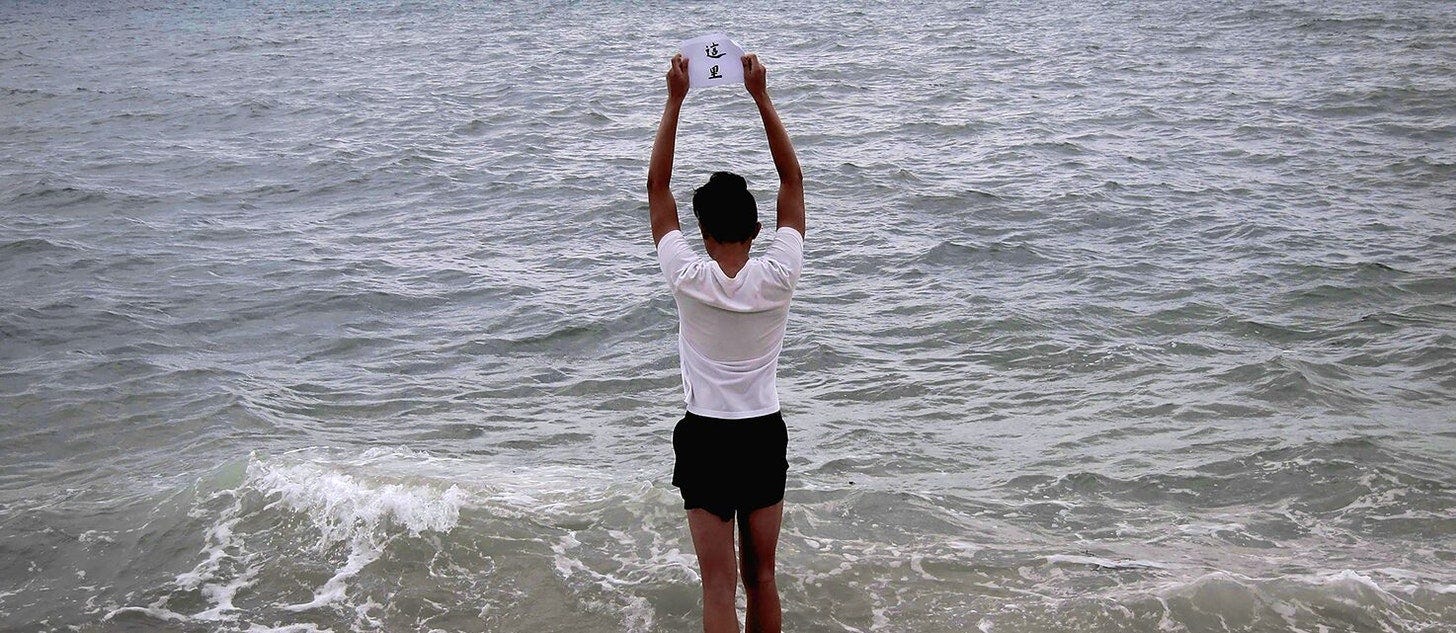

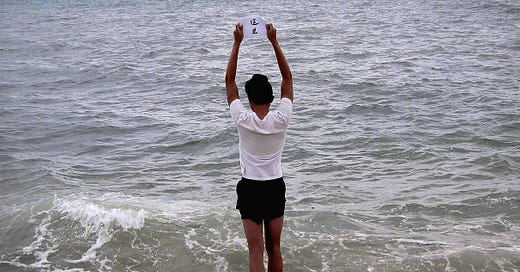

jee is sitting on a stool in the narrow road behind the Goethe-Institut Singapore. It’s twilight, and there’s a light, fine rain. Overhead, a group of birds are chattering, invisible to us but very, very audible. jee is feeding a small container with the ashes of a stack of papers they are burning. We watch as the edges of each small rectangle blackens, curls up, disintegrates. On every paper, inked in a neat hand: 這里,這里,這里. Ze leoi, ze leoi, ze leoi. Here, here, here. As the birds fuss overhead, a bat suddenly veers into the alley and collides into the glass window behind jee with a huge thunk. Disoriented but uninjured, the bat careens off and up into the air. I think of the whispers of 這里 filtering up into the realms between us, invoking jee’s grandmother but inadvertently summoning other creatures and beings into our orbit. 這里, in the traditional Chinese script: language 言 walks 辶 over to us. Here, here, here! The ashes whisper: This place, this place, this place.

It’s not unusual to see small clusters of Chinese people burning offerings around Singapore, particularly during the Lunar New Year period, the Hungry Ghost festival, or the Qing Ming (tomb-sweeping) festival. The air feels thinner around these burners and receptacles—almost like someone, or something, might come through—and you’ll see pedestrians picking their way carefully around joss papers scattered across the path, or the curated food offerings lining the pavement. jee’s offering is modest in comparison, but extremely specific—they are not invoking all ancestors, just one.

jee’s maternal grandmother, or 婆婆 (pó po), died in May 2018. Since early last year, jee has been revisiting a series of audio/video recordings they made with their grandmother in the years before she passed, when she began, unprompted, to narrate her early life and recount deeply-wedged traumas around abandonment, gender and war. This, while the both of them, grandparent and grandchild, practised calligraphy in their shared family apartment in Siglap. harbor has grown out of these written and recorded memories of their deeply intimate relationship. This is not my first encounter with harbor and its waves; I am part of the Something-Something Working Group that has followed jee’s practice and this particular work since late last year. Together, the working group has offered a space for jee to reflect on the desires, preoccupations, and difficult knots that have emerged from working on this very personal exploration; because of this I find myself more privy to the various layers of context that surround the work. I have come to read harbor and its many waves as both a passage of grief and an ongoing collaboration between jee and 婆婆 across different realms: the living, and the afterlife. Each incarnation of the work seems to explore and embody what remains of 婆婆 in a multitude of ways: her own memories, jee’s memories of her, the intermingling of both kinds of memories, how memories are reimagined, reconjured, rearranged as we turn the most precious and most painful of them over and over in our minds. A memory is as much our own making as they are a memorial of the thing long gone.

We file into 136 Goethe, a small basement room where jee will embark on the rest of the performance-ritual. If there’s a spiritual porosity to the air, there’s a physical porosity to this room. The windows are open, and sound artist Chong Li-Chuan’s soundscape has been drifting out onto the street. It’s a difficult combination of sounds to place: do we hear the sea? drilling? a drone? radio static? But there’s also sound filtering in from street-level into the project space: laughter, cursing, the screech of brakes from bicycles going up and down the gentle slope, passers-by peering in, hushed conversations, obnoxiously loud conversations. These extant sounds and noises often interrupt the quiet playback of an audio recording of jee and 婆婆’s conversations. jee has subtitled this particular exploration The TV From The Other Room. Since returning to Singapore from Berlin, and since their 婆婆’s passing, jee has moved into her room. Across the street, there is an eldercare facility where the TV is almost always playing in other rooms, muddying the sound of the TV from the family’s own living room. On jee’s departure and return, they have found themselves de-sensitised and re-sensitised to the stream-of-consciousness soundscape of infomercials and never-ending soap operas, the white noise against which so many Singaporeans grow old.

At first, I’m frustrated by the other sonic incursions in the basement studio, but eventually I allow myself to decouple from them, allow them to drift over me, to recede with the tide of other urban static. As jee and 婆婆 speak to each other in Cantonese—her meandering recollections, jee’s occasional interjections and clarifications—a patchwork portrait emerges of 婆婆’s early life. She was abandoned by her family in favour of her brother, left to fend for herself during the second world war with another female relative, had to learn how to dodge the everyday cruelties of the Japanese occupiers. Suddenly the harbour of the work’s title feels less like a symbol 婆婆’s arrival in the ports of Singapore or Hong Kong, but the harbouring of old griefs and old bitternesses that have festered and mouldered with age. jee’s patient pauses wrap gently around her as she stumbles through her past, and I think: jee is a harbour, too. 婆婆 knows she can dock here.

With an overhead projector, jee projects various transparencies with the English translation of their conversation onto the wall. A large flying ant lands on one of the slides, and a small intake of breath ripples across audience members in the room. I remember reading another meditation on grief in the wake of a loved one gone too soon—and how Chinese Singaporeans associate visiting moths with the visiting spirits of departed loved ones, especially during periods of psychic and spiritual liminality. With an extraordinary tenderness, jee lifts the struggling insect off the slide, and it flutters away. jee replaces the text on the projector with the dizzying clusters of random dot pixels you get when you turn a TV to a channel with no signal. Departures, arrivals, docking, undocking, 這里,那里,哪里? It feels like jee is tuning their self to other TVs in other realms. They are an antenna (here, here, here!) and we are watching the snow of static dissolve into the shape of a being that is jee and not-jee, 婆婆 and not 婆婆, an ancestor folded into a descendant unfolding into something the shape of a dance and not-dance. jee describes this as “being danced” by 婆婆. Not a possession but an initiation, not a trance but an invitation, not a medium but an intermediary. jee blinks slowly as the movement ritual begins, and I know 婆婆 is here, but not quite in the way I imagined she would be. I feel every hair on my body, awake and alert, drawn to jee’s verticality, the arcs of their palms and fingers, the scuff of their shoes on the concrete.

I feel my own histories and memories drawn from within myself and into the wake of this vessel of a work. I can’t help it, like the bat and the winged ant, yanked from their paths of flight into the middle of a summoning. I think of my mother dreaming of her mother, digging through the static of her unconscious in search of an image of my own 婆婆 in the wake of her death almost 15 years ago. The static on the phone, calling me far, far away at university on a different continent, telling me my grandmother was dead. My grandmother stroking the palms of my hands, saying hou hou dok hsu (好好讀書; study hard). I am a small child dozing off on my grandmother’s bed in Ipoh the night of the general elections in Malaysia, and the TV in the other room is playing the results of the vote. I mimic the cadences of the newscasters’ formal Malay quietly, under my breath, and in the other room my grandmother is saying something I can’t hear. I wonder if I am remembering or mis-remembering her, after all these years. I have no audiovisual record of her. Just the feeling of her silky shirts pressed against my arm, the jade bangles, cool to the touch, the medicinal, powdery smell of the sheets in her room. The re-told stories, the details massaged by the teller and the passage of time. My grandmother spending several months dressed as a boy in the caves of Perak, watching Japanese bomber planes go by during the war. I feel a deep regret for all the things I was not able to receive from my grandmother because I was there with her, but not here. All these grandmothers in other rooms at other times, behind doors we can’t open, obscured by languages we can’t speak.

And then jee blinks again... and it is over. But somewhere in the room and throughout the post-show discussion with jee and their collaborators, 婆婆 remains. I carry her presence with me for the rest of the weekend. She is always there, which is always here. 這里 (here) returns as a motif throughout the performance; jee had also pasted copies of the inked text on two pillars that frame the space in which they dance. I find out later that 這里 is what jee’s 婆婆 wrote when they asked her to write something for them in their calligraphy sessions together. A day later, on Mother’s Day, I text my mother to ask her about the dreams she’s had about my grandmother:

I wonder how long harbor might open itself to 婆婆’s departures and arrivals. When does a collaboration with the dead end—or is this work part of an eternal return? A recursive ritual like the ones we do every year? Each cycle and spiral of grief both diluted and thickened by memory and by time? I find that even the way in which I’ve written this accompanying essay rests on the rhythms of these repetitions and incantations. In a moment of preemptive grief I think—one day I will be the dreamer, and my mother the dreamee. I wonder about the rituals I will create and invoke to keep her here with me. Her letters to me that I keep in the drawer in my bedroom. The 16-minute voice recording I made, secretly, at the dinner table. That photograph of her with the flowers. The blueprint of my life folded into my mother’s life already inked into my grandmother’s DNA in that cave in Perak. My grandmother’s hand is my mother’s hand is my own. jee and their 婆婆 being danced by each other. Perhaps we are our mothers’ proxies to our grandmothers. Perhaps it is only in the spaces between generations that we are able to trace the scars that make our wounds our own.

This wave of harbor was presented on May 7. It was organised within the frame of the ARTEFACT creative residency programme, hosted by Dance Nucleus (Singapore), and supported by Goethe-Institut Singapore (as part of RECONNECT) and the National Arts Council, Singapore. Another wave of harbor will be presented at Tanzfabrik Berlin in February 2023.

![A series of WhatsApp text messages. Me: “mum this is really random, but how often have you dreamed / do you dream of popo”. Mum: “Yes! A few times haha.” Me: “Awww! What do you usually dream of when you dream of her, like what is she doing” Mum: “Oh dear forgot lol. Let me see if I wrote anything down in my note haha” [I have left a ‘heart’ emoji on this message] A series of WhatsApp text messages. Me: “mum this is really random, but how often have you dreamed / do you dream of popo”. Mum: “Yes! A few times haha.” Me: “Awww! What do you usually dream of when you dream of her, like what is she doing” Mum: “Oh dear forgot lol. Let me see if I wrote anything down in my note haha” [I have left a ‘heart’ emoji on this message]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!S8CM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc8989b38-94f5-4551-b195-cd0184a860d9_1125x1175.jpeg)

![A series of WhatsApp messages, continued from the previous image. Mum: “wow you can like chat?” Me: “Yes! Press and hold on the message.” Mum: “I think only for iPhone haha.” [pause] “I can’t find the dream lol but I know I dreamt of popo not long after she passed away. Just an image. Then maybe once or twice a year she is in my dreams as one of the dreamees.” [heart reaction] Me: “Dreamees!!!” Mum: “Dreamer, dreamee” Me: “That’s a good word.” A series of WhatsApp messages, continued from the previous image. Mum: “wow you can like chat?” Me: “Yes! Press and hold on the message.” Mum: “I think only for iPhone haha.” [pause] “I can’t find the dream lol but I know I dreamt of popo not long after she passed away. Just an image. Then maybe once or twice a year she is in my dreams as one of the dreamees.” [heart reaction] Me: “Dreamees!!!” Mum: “Dreamer, dreamee” Me: “That’s a good word.”](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ffVT!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2e4f2163-1493-407c-800b-5b1a485a25fe_719x1280.png)